Discouraged

The lowest part of the Joseph story, in prison, falsely accused, almost rescued, then forgotten again, despairing that it may be forever.

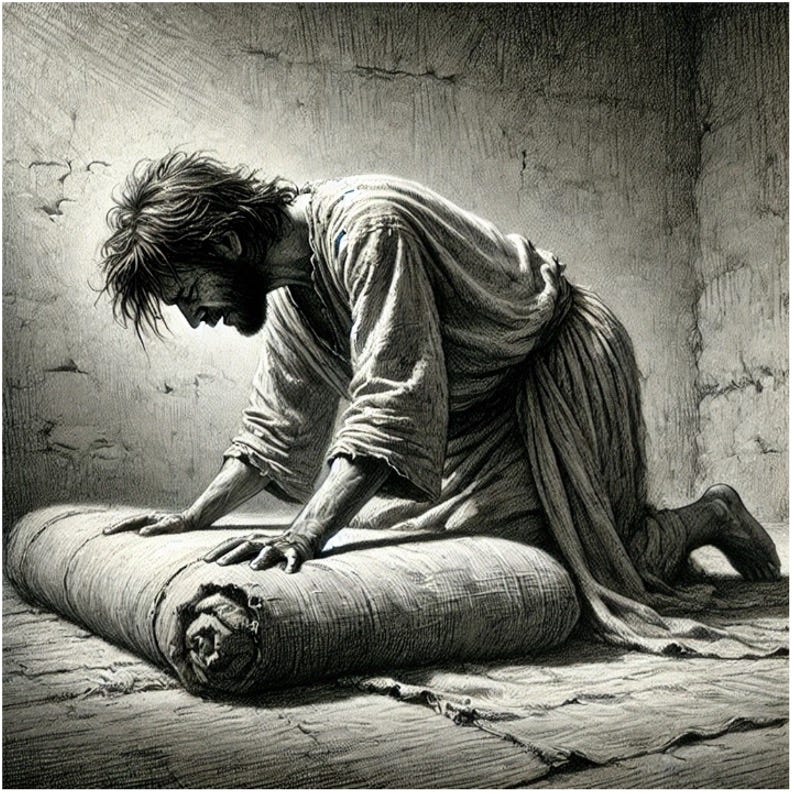

After Zuli’s ‘He made sport of me’ accusation, Joseph ran upstairs, burst into his bedroom, and fell to his knees next to his bedroll. “God, God, did you see what just happened? What am I supposed to do?” He envisioned Zuli telling Potiphar. “Please, God, can you make Zuli not … uh … no. Can you make Potiphar not ….” His voice cracked and he buried his face in his blanket to scream. He released until all he saw was white.

A half hour later he stood, every muscle taut, bent slightly at the waist, ear trained at the door, listening for Potiphar’s return.

The front door creaked. Potiphar’s voice … muffled.

Joseph’s ears roared.

Servant voices … muffled. Angry clomping up stairs.

Joseph’s stomach clenched.

The quiet. Shuffling. Potiphar’s voice. Zuli’s voice.

Joseph’s mouth dried. Seconds stretched.

Zuli shrieked in the highest, loudest voice he’d ever heard, “Joseph made sport of me.”

Jospeh shivered.

A clay pot shattered.

Joseph was reduced to a puddle of water.

Within minutes, guards wrenched him from his room, shoved him down stone steps, and dragged him before a maniacal Potiphar. Joseph lifted his head to see fellow servants gathering around. His eye caught a figure in the back row, someone he knew well, someone with a sly smile on her face, someone dangling a robe in her hand, someone who mouthed the words, ‘Don’t mess with me, Joseph.’

Potiphar stalked back and forth, hands clenched white behind him, teeth grinding like rocks. With alcohol breath he hissed, "I rescued you from slavery, Joseph, and this is how you repay me?”

He almost crushed Joseph’s arm. “I gave you headmaster…”

He stepped back and bellowed, “But I never gave you my wife!"

After being prodded through city streets like a stubborn donkey, Joseph was pushed down rock steps and thrown into a damp, dingy dungeon. The air reeked of mold and rot. A bulky wooden gate clanked shut behind him.

With his face smushed on the hardpacked dirt, he caught his breath. His head throbbed. Then a big drop of water plunked onto the back of his neck. Uh! This is just like the cistern my brothers threw me into. He rolled over and stared at the dark ceiling, best he could tell a crisscross of palm fronds, and place his elbow over his eyes. He could see Zuli’s finger-wagging and hear Potiphar’s bellowing.

Why? Why? I did the right thing. I said ‘no’ to Zuli and this is where I end up?

The warden knocked on the gate holding a small clay oil lamp in front of him that caused his black beard to glisten. He placed three wool blankets on the cross beam of the gate and said, “It’s not what you’re used to, but these are all I’ve got.”

“Wait! You know me?”

“Everyone knows you, Joseph. You were Potiphar’s headmaster.” His kind eyes sparkled. “I also know Zuli. And you’re not the first person in here because of her.”

His words didn’t warm the room or soothe Joseph’s pain or ease his headache. But hearing that Zuli had connived before made him feel a little less crazy.

Joseph woke to an aching back and pounding head. The walls of his new home were ashy gray mud bricks that crumbled in places and had pieces of straw jutting out at odd angles. Names were etched on the wall as were tally marks that counted days. He traced his fingers over the bumpy marks, wondering who these men had been, what they’d done to get there, and if they were like him … falsely accused.

The warden dropped off more blankets the next morning and asked Joseph to do in prison what he had done at Potiphar’s house. Joseph upgraded the meals from dry bread, gristly meat, and moldy vegetables to less dry, less gristly, and less moldy. Even though he was in charge, he rarely saw the sun, he almost never stretched his legs, and he was always cold. After five years of this, he came to a grim realization: Men died in places like this without anyone ever knowing it.

Many nights he would recount his father's ominous tent-prayer: "God, strengthen this boy ... no matter how dark the nights get or how lonely he feels…." How did he know how dark it would get … or how lonely I would feel? How did dad know?

He also replayed his father's dreams, especially the one about wrestling with God. Jacob had told him of that night at the Jabbok River, returning the family to Canaan, when an angel wrestled with him until dawn. They matched each other move for move—legs tangled, grips peeled off, and bodies twisted in the dust. By morning, they were both exhausted and the angel said, “Let me go.”

“Not unless you bless me,” Jacob insisted.

"Yes. I’ll give you the name Israel,” the angel said, “because you have prevailed. You, Israel, have struggled with God and men—and have overcome."

This story burned in Joseph's blood because that’s exactly what prison felt like: Wrestling. He wrestled with whether he’d ever get out. He wrestled with why he was even in there. He wrestled with whether his seventeen-year-old dreams meant anything. Or even that robe … did it signify anything? Or was it just a dad wishing great things for his son.

And beneath all these questions grew something darker. It felt like a poison in his body, a simmering, a smoldering thing. It was a burning resentment toward Zuli, Potiphar—and his brothers who started all these bad things.

One day Pharaoh’s guards showed up at the prison with thick leather breastplates on, curved swords at their waist, and brass helmets almost covering their eyes. They delivered two clean-shaven men with purple trimmed robes.

One was the chief cupbearer for Pharaoh. He poured all the king’s drinks and then tested them for poison before handing them to Pharaoh. He was tall and slender, with a thin, oiled mustache that curled up at the ends.

The other new prisoner was Pharaoh's chief baker, a stout man with thick forearms from kneading dough and hauling sacks of grain.

The cupbearer told of the mistake that landed him in prison: He’d tripped and spilled rich burgundy wine on a visiting queen’s white silk dress. The baker forgot to add yeast to Pharaoh’s favorite snack, a barley cracker, and when the king chomped into the rock-hard treat, he broke a bottom tooth.

After a couple months in prison, under Joseph’s supervision, their hands were calloused and beards were full.

One morning, both men lingered in their cells with long faces. The cupbearer explained their morose, “Last night we both had disturbing dreams but there’s no one to interpret them.”

“Well, doesn’t interpretation belong to God?” Joseph asked. They stared blankly, not knowing Joseph’s God. “Tell me your dream.”

The cupbearer explained, “I saw a vine with three branches. Each one budded and blossomed into ripe grape clusters. I squeezed the clusters into Pharaoh’s cup and placed the cup in his hand.”

“This means that in three days Pharaoh will lift up your head and restore you to your position,”

“But!” Joseph held his finger high. “Remember me and mention me to Pharaoh so I can get out of here. I’m in this country because I was sold into slavery in the land of the Hebrews. And when I served Potiphar, I did nothing wrong.”

“Yes, yes. I will tell Pharaoh about you.”

The chief baker explained his dream. On top of his head were three baskets of bread. Birds flittered around and gobbled up all the goods out of the top basket.

Joseph’s face fell and he turned away.

“Wait! What?”

Joseph remained turned away.

The baker clamped his thick hand on Joseph’s shoulder and pulled him around. “Please tell me.”

“I’m sorry,” Joseph said. “This dream means you will die at Pharaoh’s hand.

Pharaoh celebrated three days later and both interpretations proved true. The cupbearer donned his purple-trimmed robe again while the baker met his end.

Joseph listened carefully for the knock that night when the cupbearer would announce: “Pharaoh wants you in his service.” But no one knocked. Nor the next night. Nor the next. Once he realized he’d been forgotten, a pit settled in his stomach. How could he forget me? And why would God do this? Why give me false hope? Why bless me with interpretation but then stop there? It felt cruel to Joseph. Ten words! Ten simple words is all it would take for freedom to be his: ‘There is a man in prison who can interpret dreams.’

After near-freedom, Joseph’s wrestling got more intense. He still prayed, but his mind often wandered and he wondered if God heard even one word. He thought of Dinah, but suspected she was no better off than him. And he wondered about Benjamin, who was probably married by now, a tent full of kids, moving on with his life while Joseph sat in a place with no future.

One night, after scratching number 2,550 into the wall, marking seven full years in that place, he laid down to sleep, the steady dripping of water bringing on drowsiness. Suddenly a clear thought snapped him awake, an idea that was new to him, a feeling he’d never felt before, yet something distinct and defined. Could it be... another drop plunked next to him, might it be ... that the light inside of me is slowly being snuffed out?

*****

Then Pharaoh had a dream.

Thank you Ken, I really enjoyed hearing you tell this story this morning. I appreciate the depth of feeling of hope and despair. I'm waiting on the Lord and you have given me strength today 🙏

Love it, thanks for mentioning so. Great to hear from you.